Forensic scientists study death's timeline

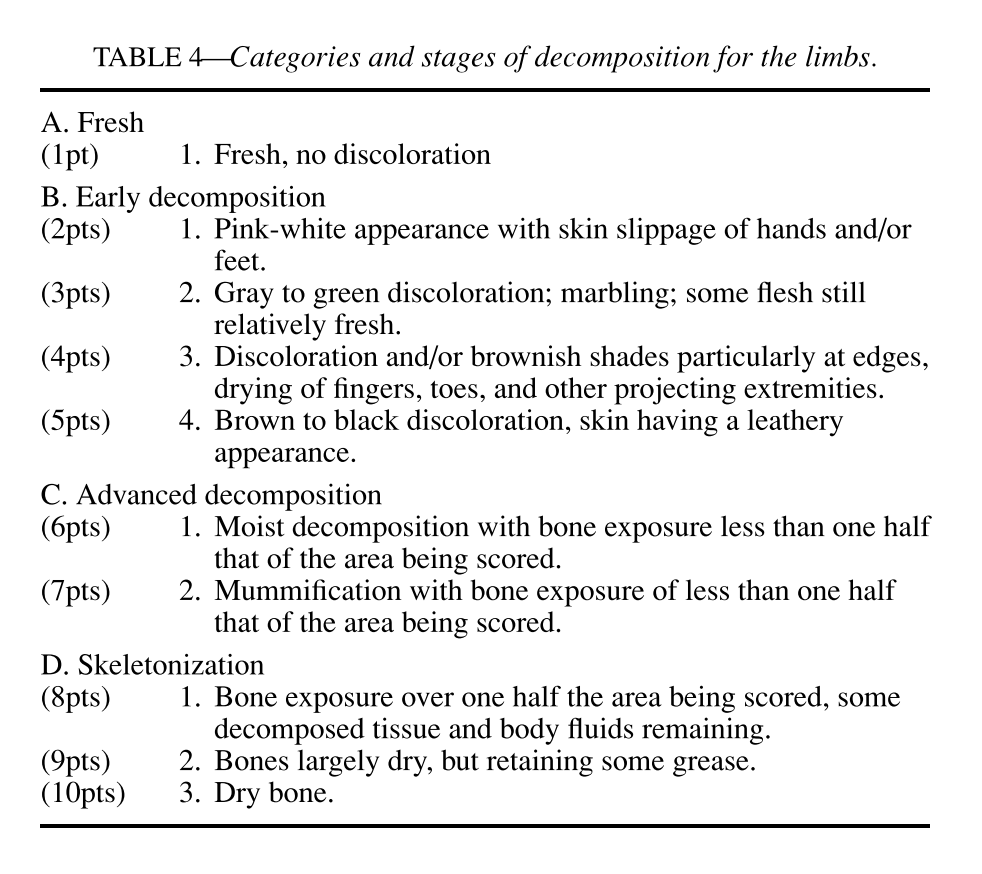

During the early stages of decomposition of the limbs, the body takes on a pink-white appearance with skin slippage of hands and/or feet, and then moves to a gray to green.

I have long believed that forensic scientists could effortlessly determine the time of death from a decomposing body, and that anthropology forensic science experts, dealing with skeletons in ancient tombs, could confidently pinpoint the century of death.

However, my visit to the Australian Facility for Taphonomic Experimental Research (AFTER), located in a secret location in Western Sydney near the Blue Mountains, revealed a more fraught reality.

Since 2016, a diverse team comprising forensic scientists, biologists, pathologists, chemists, anthropologists, odontologists, and police has conducted innovative studies and rare training exercises at AFTER on whole-body donors.

The raison d’etre of the facility is multi-disciplinary and all the forensic disciplines are represented. They study how tattoos change, how bodies move, different odours, DNA and much more.

On one visit, I spent time with Dr. Maiken Ueland, a forensic chemist, as well as forensic science and anthropology students.

Maiken is an emerging leader in the field of forensic taphonomy, where she uses analytical, biochemical, and spectroscopic techniques to conduct human post-mortem investigations.

At the site, I watched on as she and the students were studying four donors who had been buried under rubble. They were watching how they decompose and making various measurements for different projects.

Maiken explained that if a person has just died, it’s a lot easier to determine the time of death, and the pathologist will be quite good at it. “And then once you get to a couple of weeks, the insects are really good—the entomology is also quite precise. It’s still being worked on but quite good.”

“But then once you get beyond that, it gets quite, quite difficult. Once it’s weeks to a month, it gets very difficult to get a very precise time. It’s more like you get ranges and the longer the time goes, the larger the ranges. So if you find like a skeletal sample, the ranges could be really large.”

One tool that is used is the ‘total body score,’ which was developed by Mary Megyesi, Stephen P Nawrocki and Neal H Haskell in the US in 2005.

The score tries to measure decomposition over time, also taking temperature into account.

For the study, 68 human remains cases with a known date of death were scored by studying crime scene photos. Their decomposition revealed a vibrant, colourful and busy world, as you can see from Megyesi’s paper below.

As the paper decribes it: “Remains found outdoors were the most common in the dataset, accounting for 57 cases. These came from a variety of settings including woods, fields, and ditches. Thirteen cases were found in full sun, 15 in shaded areas, and 29 in areas that received a mix of sun and shade. Remains found indoors were also included in this study.”

The Megyesi et al. study established a benchmark and was significant in its utilization of human subjects. However, over the years, there has been some criticism of the score, including the acknowledgment that people decompose differently in various climates.

For instance, if left to the elements in Western Sydney, you are more likely to mummify than if in the US.

As Maiken remarked about the determination of the time of death: “It’s a major challenge in a lot of investigations because it’s so hard.”

I now recognize that whenever the 'time of death' is discussed in murder cases or on ancient history documentaries, I need to be more vigilant about the claims.